modern approaches

to Performing Sephardic Music

Dumbek (drum)

Pontic Lyra

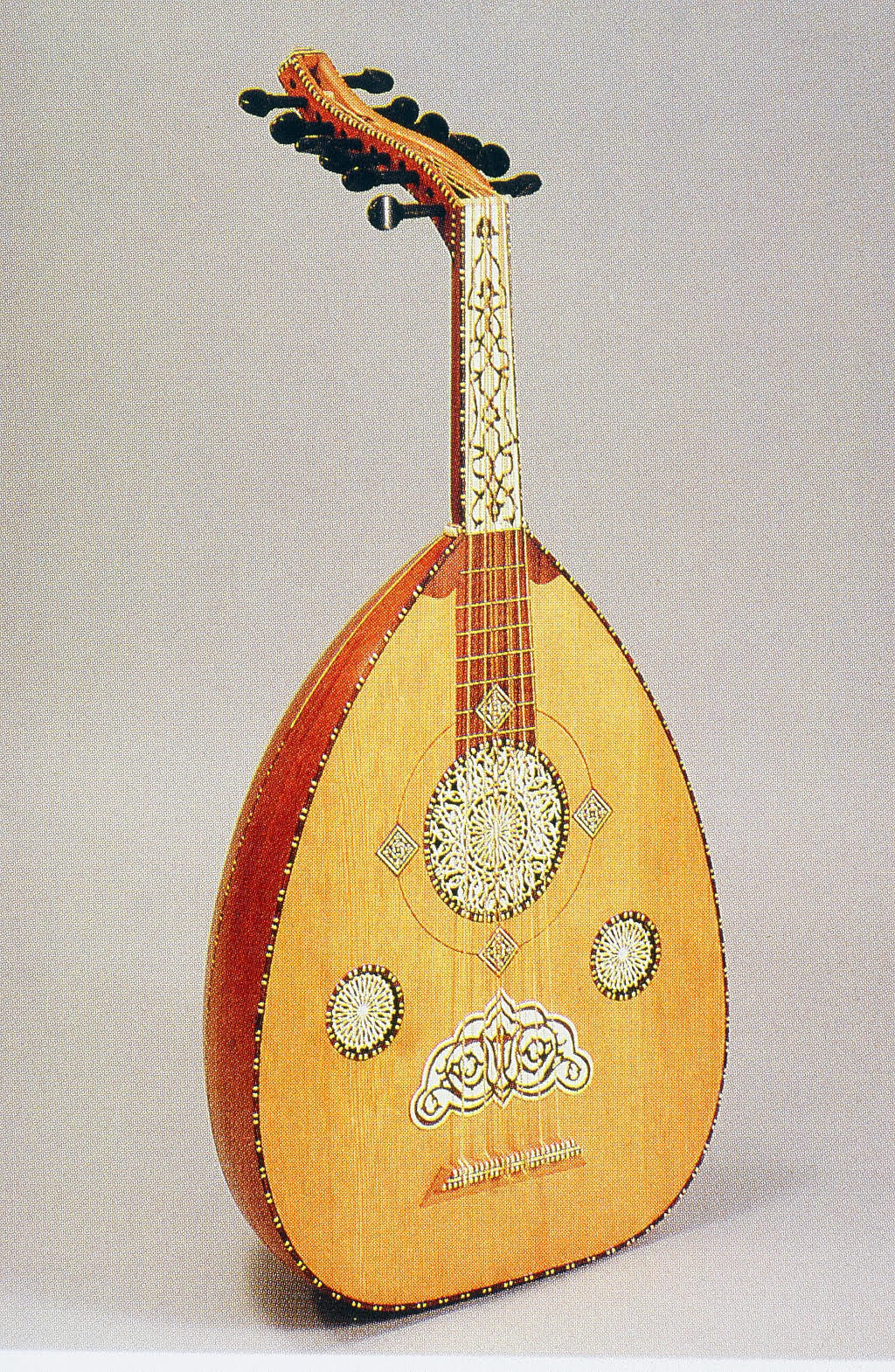

Oud

Ney

Performers whose ancestral background is not Sephardic (and even some who are connected genetically) who are drawn to this musical tradition face a variety of stylistic choices in presenting this repertoire. Prior to World War II there were large, vibrant communities of Spanish-speaking Jews in the former Yugoslavia, Greece, and Turkey, and in some ways the music from those communities is more familiar to musicians whose training and background is rooted in Western European key structures, harmonies, and meters. There are some performers who gravitate toward a Middle Eastern approach—after all, some of the Sephardim who fled Spain did end up in Palestine, Egypt, and other Middle Eastern regions—with an emphasis on Arabic modes and rhythms, employing such instruments as the oud (ancestor of the lute) and ney (an end-blown flute). Because a significant number of Spanish Jews fled to North Africa from Spain beginning even before the 1492 Edict of Expulsion some performers draw heavily on musical influences from Morocco, Tunisia, and other countries in a region most accessible to Spanish Jews.

TRIO SEFARDI’S PERSPECTIVE

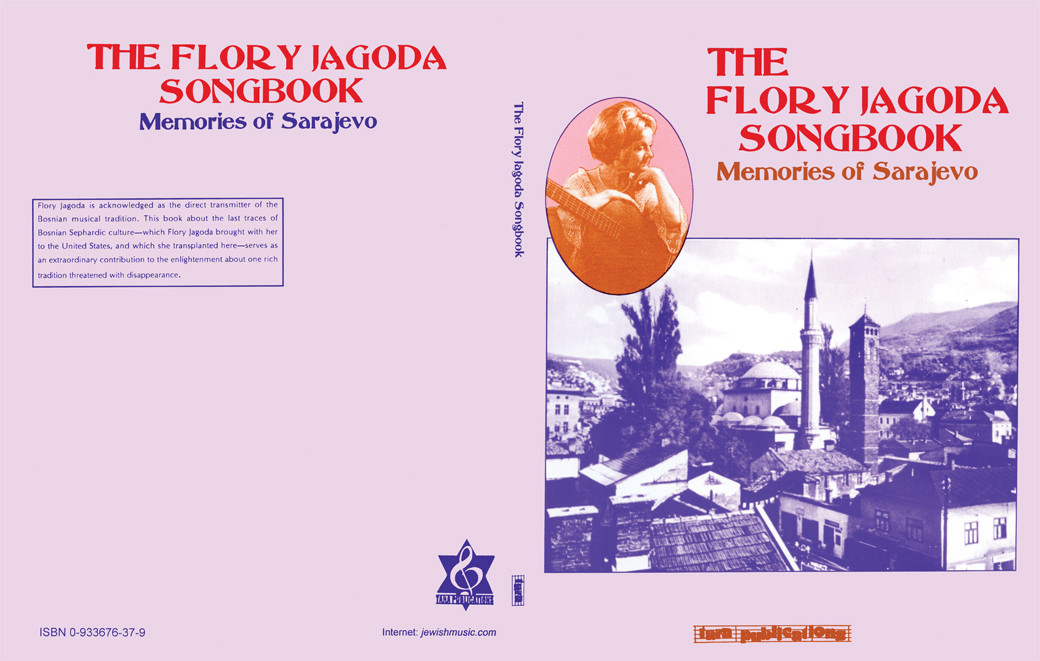

Trio Sefardi members bring to this music a combination of backgrounds, including jazz and traditional music (Susan), and early music and various other Western traditional musical styles (Tina and Howard). Perhaps most significantly, we reflect the strong influence of Bosnian-born singer, composer, and song-keeper Flory Jagoda, with whom Susan and Howard performed for more than a decade. The majority of our songs feature harmonies and chords that our varied musical influences have in common. While the nylon-strung classical guitar is featured prominently throughout our repertoire, we also make use of the Renaissance violin and lute, the bass viola da gamba, and the medieval rebec. The kamenj or Pontic lyra, a bowed three-stringed fiddle popular in Greece and Turkey, as well as the dumbek, a hand-drum popular throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey, are employed in many of our songs. The tambourine, which we also use, has long been considered important in Sephardic culture; Flory Jagoda points out that tambourines were a traditional first gift to a new bride in Sephardic families. The fifteenth-century Spanish monk and chronicler, Andres Bernáldez, wrote that as the Spanish Jews were going into exile in 1492 the rabbis urged the women “to sing and play their tambourines, to keep the people’s spirits up.”

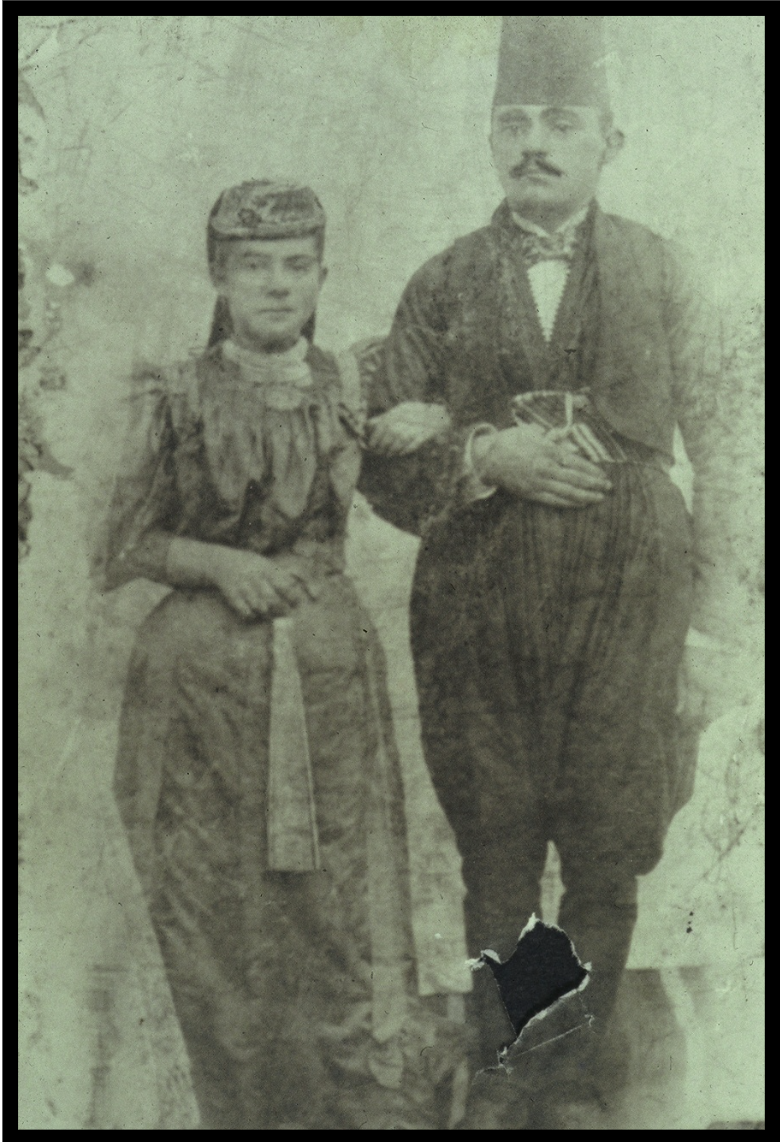

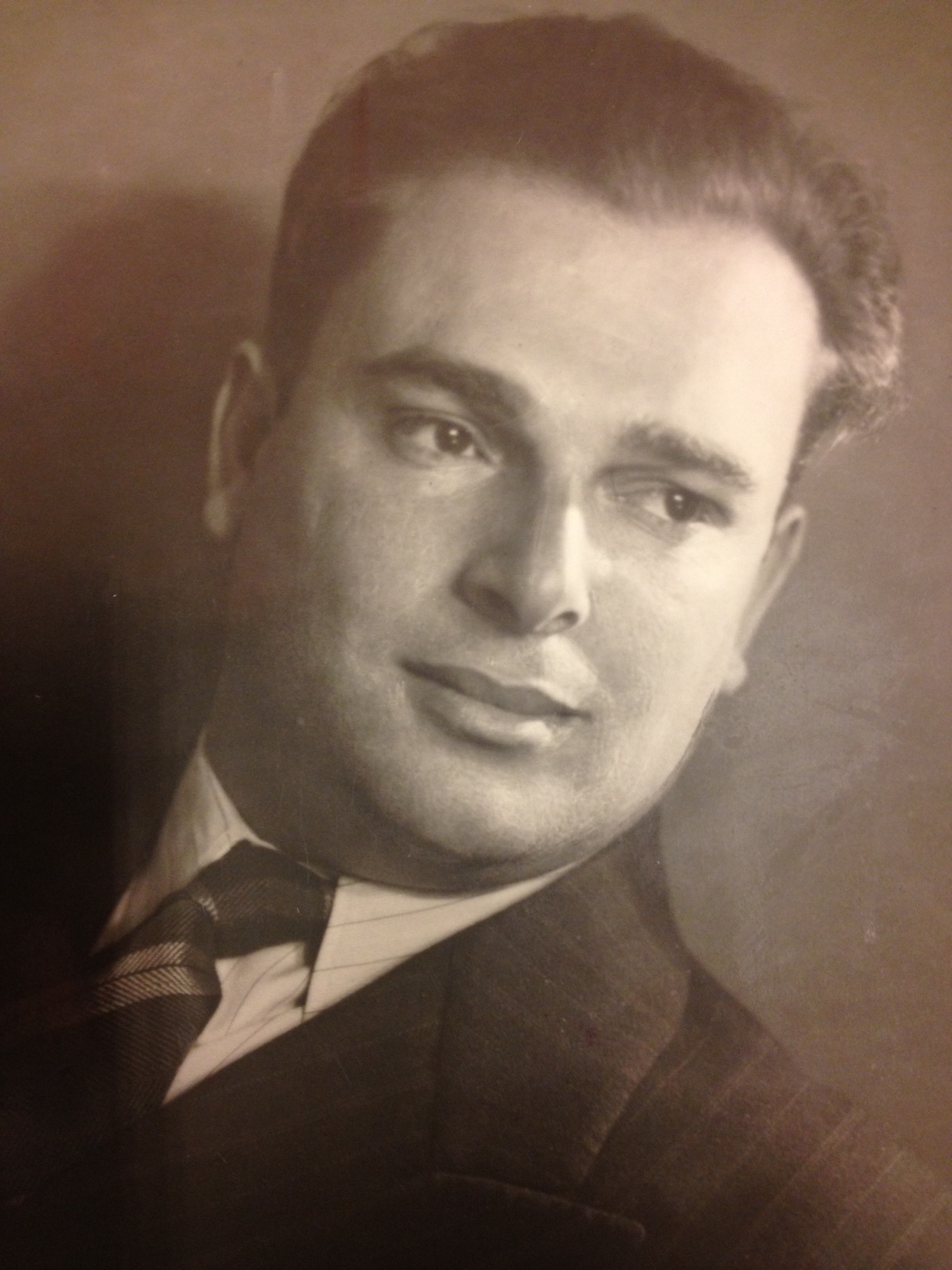

The Altarac Family

Flory Jagoda with members of Trio Sefardi

Music as a Way of Life

Flory's Tiya Estreya

Flory's Nona and Nonu, Berta and Sambul Altarac

PERFORMERS, TIME AND PLACE

The singing of Sephardic songs has always depended on time, place, and the personality of the performers. Indeed, in the centuries of Sephardic song history, its singers were not really performing the songs in the modern sense. Music was instead an everyday expression of a culture and a way of life. The songs were sung for personal amusement and in family settings, to relate history, and to teach lessons; in addition, there was and still is a rich tradition of liturgical songs and prayers, known as piyyutim. In her singing, Flory employed a type of trill or vocal ornament that she taught to Susan, and that particular element is clear in Susan’s own performances and recordings.

The old Sephardic way of life, sustained in a diaspora that lasted five centuries, has nearly disappeared and few remain who sing these songs as they would have been heard even half a century ago. Since the advent of recordings and radio in the early twentieth-century, traditional music from cultures the world over has been explored (and in some cases exploited) by performers with a far broader range of musical influences. Contemporary technologies—compact discs, the radio, the computer, desktop publishing, the internet—are now common tools used to preserve ancient traditions. The result is that there are many approaches to performing the music of the Sephardim, some of which remain faithful to earlier styles, others of which strike out in new directions. The positive result is that the music and the language in which it has always been sung, commonly known now as Ladino (Judeo-Espanyol is more accurate) is alive and the language embodies the essence of this venerable cultural tradition.

IRRESISTABLE MUSIC

Non-Sephardic performers, like the members of Trio Sefardi, whose ancestors came from the better-known Ashkenazi communities of Eastern Europe, have begun to perform and record Sephardic songs, just as people of many nationalities and backgrounds now play Irish, Cajun, and other traditional repertoires. Musicians today are surrounded by music of all kinds, from many peoples, and such attractive, vibrant music as these Sephardic songs can prove irresistible to musicians from other cultures. It is important to bear in mind, though, that differences of interpretation exist even within Sephardic communities. A Turkish Sephardic Jew of my acquaintance once remarked that a certain Jewish singer from the Balkans in no way represented “real” Sephardic singing; in his view only Turkish singers are authentic. Some folklorists maintain that the use of any but the simplest instruments (like the tambourine) violates the spirit of Sephardic tradition. While it is true that much of the music would have been sung unaccompanied, ample evidence from the thirteenth-century onward shows that instruments of all sorts were used by Sephardic musicians when instruments were available to them.

An illustration from the fourteenth century Barcelona Haggadah shows musicians playing plucked and bowed string instruments, a bagpipe, and a small drum, but we have no way of knowing how common that was; unaccompanied singing was certainly the most common way of presenting songs. A group of people singing together probably would have used whatever instruments came to hand and may well have incorporated vocal harmonies; such practices were well known in the Balkans when Flory Jagoda was a child. The accordion (known as the harmoniku) was quite popular among the Sephardim of Bosnia; it was, in fact, the first instrument that Flory played. In the end, as long as performers respect and understand the history and background of the music, sing the songs in Ladino, and continue these centuries-old traditions, Sephardic music will remain alive and even refreshed by contemporary musicians from many backgrounds. We, the members of Trio Sefardi, like to keep in mind the cherished words of Flory Jagoda’s Nona (grandmother), Berta Altarac: “Si nu puedis meter la alma, nu kantis.” (If you can’t put your soul into your songs, don’t bother singing.)

INCORPORATING INFLUENCES

Nothing in music is done in isolation, not now, nor in past centuries. Before their exile from Spain, the Sephardim heard the music of their Arab and Christian neighbors and they would have freely incorporated such influences into their own songs. Most musicologists agree that few if any Sephardic songs popular now are more than two centuries old, though it is possible, even likely, that some song texts date to earlier centuries. That said, song themes about historical events, holidays, love, loss, and daily life were a constant in the Sephardic song tradition; indeed, such themes are found in traditional singing all over the world. While there was a certain amount of stability in Sephardic communities in parts of the old Ottoman Empire (namely Turkey, Greece, and the former Yugoslavia) and in North Africa and the Middle East until the twentieth-century, it’s clear that national and regional borders were crossed freely by singers and their songs.

Early twentieth-century recordings made in southern Europe, Turkey, and the United States bear witness to the influences of the various regions where the Sephardim settled. The main distinction between a Greek rebetika, say, and Sephardic song lies in the use of Ladino. The place of origin of some songs can be discerned, such as when specific place names are cited (see “Ragusa” or “Bre Sarika” on our recordings) or phrases in Turkish occur (as in “Por la tu Puerta”); but songs traveled with the singers, and while a musicologist like I.J. Levy may have identified a specific town or city where he heard a song, that song might have traveled a long way over many decades and national borders before Levy heard it.

The Flory Jagoda Songbook

Levy

FLORY JAGODA

By the 1930s the radio and sound recordings gave even some of the most isolated communities (such as the Bosnian village of Vlasenica, where Flory Jagoda spent much of her childhood, access to new sounds. Flory’s songs sometimes show a distinct Latin rhythm of the tango and rumba that she and her family would have heard on the airwaves. So it is that Trio Sefardi’s interpretation of such songs as “Una noche al bodre del mar” and “Madre miya si mi muero” pay homage to such influences. Even Flory’s best-known song, “Ocho Kandelikas,” can easily be imagined as a tango (check out the recording of this song by the Latin-inspired band Pink Martini for a good example). More recent influences on Sephardic song interpretation might include lush orchestrations in the style of Nelson Riddle, as well as the use of electric guitars, upright bass, saxophone, flute, and drum kits.

REFLECTION THAT SPRINGS FROM HEARTFELT EMOTIONS

In 1992, five centuries after the exile of the Jews from Spain, King Juan Carlos apologized to the Sephardim and invited them back to Spain, and some have taken the king up on this invitation if they have enough documentation to prove their family’s Spanish origins. Interest in the Jewish culture of Spain has increased, both there and elsewhere. Recordings of the music have become more available, including a growing number by performers with Sephardic ancestry. The performances by Trio Sefardi are not re-creations, though we do perform music composed and arranged by Flory Jagoda more or less as she taught them to us. Our interpretations of songs from other sources in no way attempt to present the music as it might have sounded at the time of exile, or any time since in Sephardic communities. At its best, our presentation of Sephardic music can be likened to an artist’s rendering of a scene from nature or a portrait: not the thing itself, but a reflection that springs from heartfelt emotions and the technical abilities to convey these songs and their meanings to others, rendered with deep respect for the those who bequeathed to us such a splendid legacy.