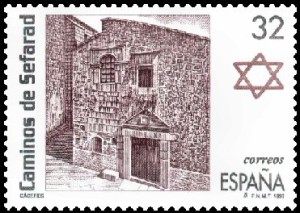

The Sephardim, the Jews of Spain, lived on the Iberian Peninsula for fifteen centuries. Expelled in 1492 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the Sephardim settled in North Africa, the Middle East, France, Italy, and parts of northern Europe, but were welcomed most warmly in the Ottoman Empire. In exile they maintained their language, Ladino, and their oral culture. Songs were passed through the generations, usually by women, and new songs were composed about love, loss, daily life, holidays, and history.

Jewish history is replete with stories of exile, hope, faith in redemption, and the yearning for an eventual return to the Holy Land. For the Jews of Spain, the concept of exile and return is embodied in their very name, which comes from a passage in the book of the prophet Obadiah, who wrote, “The exiles of Jerusalem who are in Sepharad shall possess the cities of the Negeb.” Whether Obadiah was in fact referring to the Iberian Peninsula or to some other place is not now known, but eventually the term Sepharad was applied to the Iberian Peninsula, and the Jews of that region came to be known as Sephardim, though the name seems to enter common use only after the expulsion.

Jewish history is replete with stories of exile, hope, faith in redemption, and the yearning for an eventual return to the Holy Land. For the Jews of Spain, the concept of exile and return is embodied in their very name, which comes from a passage in the book of the prophet Obadiah, who wrote, “The exiles of Jerusalem who are in Sepharad shall possess the cities of the Negeb.” Whether Obadiah was in fact referring to the Iberian Peninsula or to some other place is not now known, but eventually the term Sepharad was applied to the Iberian Peninsula, and the Jews of that region came to be known as Sephardim, though the name seems to enter common use only after the expulsion.

Jews lived in Spain during Roman times, and a significant Jewish presence existed there when the Moors invaded from North Africa in A.D. 711. After the Moorish conquest, Jews settled in Spain in much greater numbers, lured by the promise of tolerance and economic opportunity. Jewish culture flourished in Moorish Spain. While Jews lived in their own neighborhoods Jewish scholarship, science, and business were integral to the larger community. Even as the Spanish gradually reconquered the peninsula, and anti-Semitism became more wide-spread, Jews played important roles in the courts and councils of Christian rulers.

By the 14th century, however, persecution and anti-Jewish riots increased as Catholic power grew. A turning point came in 1391 with a major pogrom and slaughter of Jews in Sevilla. After this massacre, many Jews fled to North Africa. Some who stayed in Spain chose conversion to Catholicism, but many of these so-called conversos maintained their ties to Judaism in secret. In 1478 the Inquisition was established to root out such so-called heresies, and all conversos risked persecution. An accusation, true or not, resulted in a summary trial. Death by burning (auto-de-fe) was a common punishment; the Inquisitors unaccountably preferred this method to the shedding of blood.

By the 14th century, however, persecution and anti-Jewish riots increased as Catholic power grew. A turning point came in 1391 with a major pogrom and slaughter of Jews in Sevilla. After this massacre, many Jews fled to North Africa. Some who stayed in Spain chose conversion to Catholicism, but many of these so-called conversos maintained their ties to Judaism in secret. In 1478 the Inquisition was established to root out such so-called heresies, and all conversos risked persecution. An accusation, true or not, resulted in a summary trial. Death by burning (auto-de-fe) was a common punishment; the Inquisitors unaccountably preferred this method to the shedding of blood.

In January 1492, Spanish forces under King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile drove the Moors from their last stronghold, the Kingdom of Granada, ending seven centuries of Moorish rule on the Iberian Peninsula. In March of the same year the Edict of Expulsion was announced, giving the Jews of Spain three months to convert to Christianity or depart. The reasons for the edict remain a subject of debate. It seems clear that the impetus came from the Catholic Church, rather than directly from Ferdinand and Isabella. The leaders of the Inquisition may have hoped that driving all Jews from Spain would free conversos from the temptation to practice Judaism. Confiscation of Jewish wealth was another possible motive. Xenophobia and the desire to rid the country of all infidels, Arab and Jew alike, also played their parts, as did the age-old anti-Semitism, hardly unique to Spanish Christians.

The bitter irony of this version of racial purity is that by the end of the fifteenth century the population of Spain was so mixed by extensive intermarriage among Christians, Jews, and Muslims that the “ethnic cleansing” (to use a more contemporary term) envisioned by the perpetrators of the Inquisition was virtually impossible to achieve. Over the centuries, questions of mixed ancestry have hovered over such historical figures as Christopher Columbus and even over Torquemada, the Grand Inquisitor himself. Eventually, large numbers of conversos lost their rights and property. Thousands were humiliated and tortured; thousands more were executed. Those who preferred exile to coerced baptism departed in poverty from a land inhabited by Jews for fifteen centuries. Spain thus became the first European country with the dubious distinction of having rooted out an entire people and its culture.

Andres Bernaldez, a Spanish monk who witnessed the expulsion, wrote the following account: “They were abandoning the land where they were born. Small and large, young and old, on foot, atop mules or dragged by wagons, each one followed his own route toward the chosen port of departure. They stopped by the side of the road, some collapsing from exhaustion, others sick, others dying. There was not a person alive who could not have pity for these unfortunate people. Everywhere along the road they were begged to receive baptism, but their rabbis told them to refuse, while urging the women to sing and play tambourines to keep their spirits up.”